A feminist analysis of Bumble: A reinforcement of heteronormativity?

For: Critical Media Studies

Dr Radek Przedpełski

By: Rose Connolly

Bumble is a dating app founded by Whitney Wolfe Heard in 2014. The founder has marked the app as “100% feminist” (Yashari, 2015, para. 8) and its definitive feature is that women must message men first in opposite sex matches. As of 2023 Bumble has 50 million users (Curry, 2023), and now caters towards friendship and business matches - Bumble BFF and Bumble Bizz respectively. Despite catering for other markets their main focus remains Bumble for dating. The primary aim of this essay is to analyse Bumble (for dating only) from a feminist view. The app certainly has positive qualities however the focus of this essay is to examine its shortcomings. As discussed throughout this essay much of these shortcomings stem from their ‘women message men first’ feature, and the ideals this was built on. The essay is written primarily with feminist analysis in mind, and to a lesser extent queer analysis. This essay does not touch on race however this does not mean there are no issues here - multiple studies have discussed race discrimination in dating app algorithms (for example, Nader, 2020, Narr, 2021), to name just one such issue.

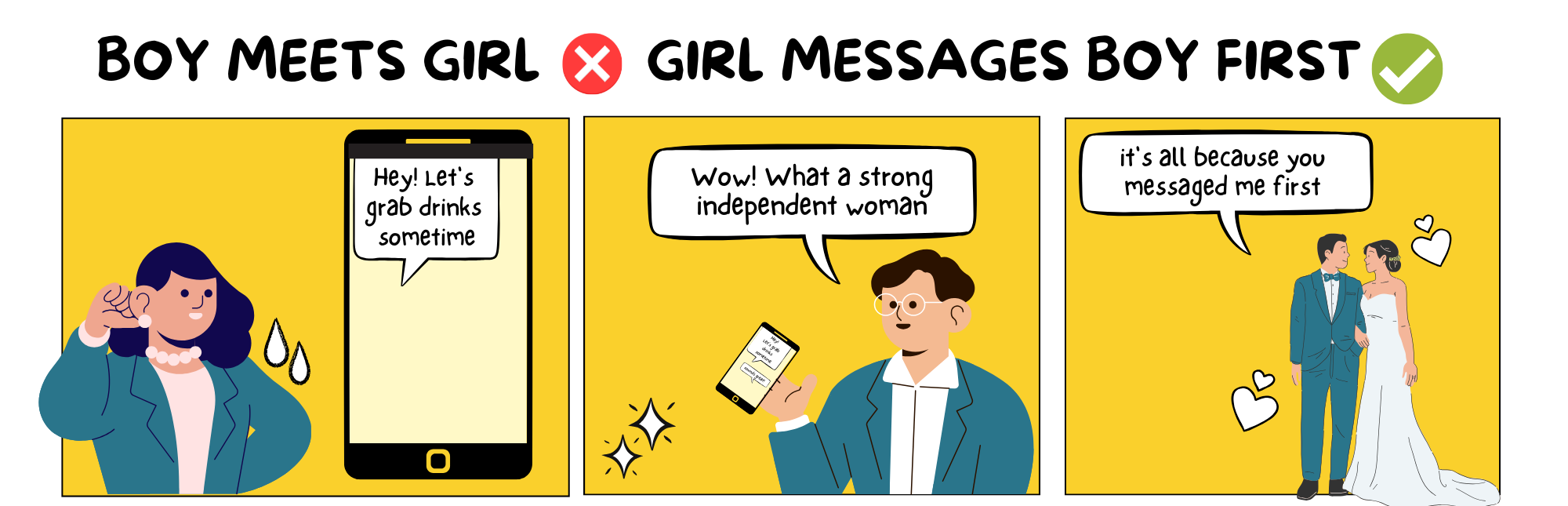

In general there are two reasons Bumble implemented a ‘women message men first’ feature. The first was to avoid the harassment and danger typical of dating apps. The second is to challenge traditional power imbalances. The founder has mentioned these reasons in various interviews (The Atlantic, 2016; Yashiri, 2014) and they are also explained on the app’s website (Bumble, n.d.). A study of 14 female users of the app found that women generally use the app for these same reasons. These women used Bumble to avoid negative experiences with men and to challenge power imbalances (Pruchniewska, 2020). While dating apps have become the modern solution to finding both hookups and meaningful relationships these apps can be unsafe and hostile for some users. Women often are subject to receiving unsolicited messages and pictures on dating apps, more so than men (Duggan, 2017). By choosing which men to message the risk of harassment is lower for women using Bumble. By starting the conversation off respectfully female users have found the conversation is more likely to continue that way (Pruchniewska, 2020). This brings us to the first issue with Bumble’s feminist claims. It cannot be denied that women are harassed on dating apps. But the experience is much worse for those with marginalised identities (Lenhart, Ybarra, Zickuhr, & Prive-Feeney, 2016) such as trans and queer women as well as users who are non-gender conforming. The ‘women message men first’ feature may solve harassment, but only for women matching with men. In other cases either party can message first and the risk of receiving aggressive or hostile messages remains. Thus Bumble seeks to solve a problem for only a small subset of the people who experience the problem. Thus the feminism Bumble embodies is only for straight women, and thus cannot be deemed truly feminist. The second reason (Pruchniewska, 2020) women use this app is to challenge stereotypical gendered dating norms, that men always should “make the first move”. The origins of the app, and its defining feature is based on countering a heteronormative power dynamic. This brings to mind the concept of “compulsive heterosexuality” (shortened to comphet) which was coined in Adrienne Rich’s influential 1980 paper “compulsive heterosexuality and lesbian existence”. Comphet is the idea that heterosexuality is the natural, default sexuality and any other is deviant from the norm. Comphet has been reinforced in society by and for men for the personal and financial benefits a patriarchal society allows them (Rich, 1980). Bumble’s most well known feature helps women feel confident and empowered by messaging men first but. However by the very nature of this feature this empowerment is reliant on the presence of men. This speaks to an extension of comphet - the idea that women’s sexuality and reproductiveness (and in this case empowerment) exists only with and by the presence of men.

Bumble’s most well known feature is inclusive only of heterosexual relationships, albeit one where the traditional power dynamic of male/female relationships has been shifted. It is a challenge of the binary stereotype of masculinity representing power and femininity representing powerlessness (Przedpelski, 2023). However an app built upon these ideals neglects queer relationships. This feature is fully binary in its approach and built upon gender as two oppositions. The app addresses a power dynamic that only exists in heterosexual relationships. Bumble’s (self-declared) defining attribute is that women message men first in opposite sex relationships. This automatically presents the follow-up question “well what about two women?”. The answer is that in same-sex matches either person can message first. Bumble of course provides functionality for same sex matches but the fact remains that they are most well known for the’ women message men first’ feature. “Oh Bumble, isn’t that the app where women have to message first?” They have embraced this reputation and do not market any other such innovative feature for queer matches. The suggestion of heterosexuality as the main sexuality is a manifestation of compulsive heterosexuality. The central ideals the app is built on reinforce heteronormativity. The suggestion of non-heterosexual matches as being a follow-up question or an afterthought is stigmatising and reinforces queerness as deviant or the ‘other’. It can also be argued that Bumble is idealistic in challenging the traditional power imbalance existing in heterosexual relationships. By women messaging first Bumble attempts to shift the power from men to women. It should be investigated how much ‘power’ can be given to someone simply by giving them the ability to initiate a conversation (Young & Roberts, 2021). A traditional male-female relationship involves men being the pursuer and women the pursued. Research shows that this traditional approach to heterosexual relationships still remains intertwined in society (Lynn Jamieson, 2013; Chrystie Myketiak, 2015 in Young & Roberts, 2021). It is not then a question of whether power imbalances exist in heterosexual relationships. It is however a question of whether the approach Bumble takes to solving it is impactful enough.

In addition, Bumble founder has expressed hope this shift not only sets the tone for one conversation but entire relationships (Yashiri, 2015). The importance of the initiator of just one conversation should be investigated, and whether any such effect caused can persist throughout the lifespan of the relationship. The idea that a long-existing power imbalance can be solved by such a small change seems an unrealistic approach to something caused by ingrained and, for a long time, unquestioned belief systems. Exploring another reason for the implementation of the “women message men first” feature - Whitney Wolfe Heard has said that the app is made such that men are not put in a position to feel angered at being rejected by a woman they have messaged first (Yashari, 2015, para 12). By the women always messaging first the man “feels flattered” (Yashiri, 2015, para 12) and the vulnerability of putting themselves out there is removed from them. It can be argued then that the app serves to minimise the effects of fragile masculinity. Can we simply solve harassment stemming from fragile masculinity simply by placing a constraint on who initiates the conversation? Again this seems idealistic. And can an app designed to placate male rejection sensitivity be deemed “100% feminist”? It begs the question of who the app was designed for. Not to mention that the pressure of messaging first is removed from men and then put on the woman. Of course this pressure was put on men by cultural norms - the man doesn’t have to message first, however he usually does. The app feels like a quick-fix - a technical sidestep around the real issue here - that women shouldn’t be subject to aggression that stems from rejection in the first place, no matter who messages first.

Bumble’s place in the Waves of Feminism

Bumble was launched in 2014, 3 years before the influential “Me Too” movement that is characteristic of the beginning of fourth wave feminism. The ideals of the app are not completely characteristic of fourth wave feminism but a mixture of both third and fourth wave. It is still debated when exactly fourth wave feminism began (or if it has even begun yet), and what it entails. However broadly speaking fourth wave feminism focuses on sexual harassment, rape culture and intersectionality. It is facilitated by the use of social media, which rapidly accelerated the growth of the MeToo movement (Anderson, 2018). Being a dating app, Bumble is in the realms of being a form of social media. Much of its marketing takes place on Instagram and Twitter. One of the main reasons women use Bumble is to avoid aggressive messages from men (Pruchniewska, 2020 & Yashari, 2015). The focus on limiting harassment is mildly suggestive of a fourth wave feminist app, however as argued below it is much more representative of third wave feminism. Third wave feminism challenged gender norms and moved towards a society in which women could be powerful and assertive. It incorporates intersectionality but it took the fourth wave to fully expand this concept. Third wave feminism questioned what womanhood represented and argued the notion that traits were characteristically feminine or masculine (Snyder-Hall, 2010). Bumble’s defining feature is based on these ideas - “Bumble was first founded to challenge the antiquated rules of dating” (Bumble, n.d.). The idea of assertiveness being a masculine trait is confronted by their ‘women message first’ feature, making Bumble a truly third wave feminist app. Perhaps it takes a while for culture to ‘catch up’ with the ideals of the current wave of feminism while fully upholding the more ‘sunk-in’ ideals of the previous wave. Bumble covers the third wave of feminist ideals very well but lags slightly behind with the fourth wave. Perhaps the app will shift to a more fourth wave approach in the future and consider a broader female experience.

Final Words

Is Bumble a feminist app? Once again two reasons for its main ‘women message men first’ feature are;- To prevent harassment women often are subject to from men on dating apps. This can take the form of aggressive messages, unsolicited pictures or even manifest ‘offline’ with men stalking women who have rejected them (Fansher & Eckinger, 2021).

- To shift the unhealthy power dynamic traditionally seen between a man and woman: The pressure put on men to be the pursuers (and message first) and women to be the pursued (to not message first), in fear of being seen as pushy or too confident.